The equity policy of the 2021 Transportation Master Plan (TMP) update sets as one of its goals to “support everyone’s ability to work, participate in public life, and meet daily needs.”

Written by Tara Mills.

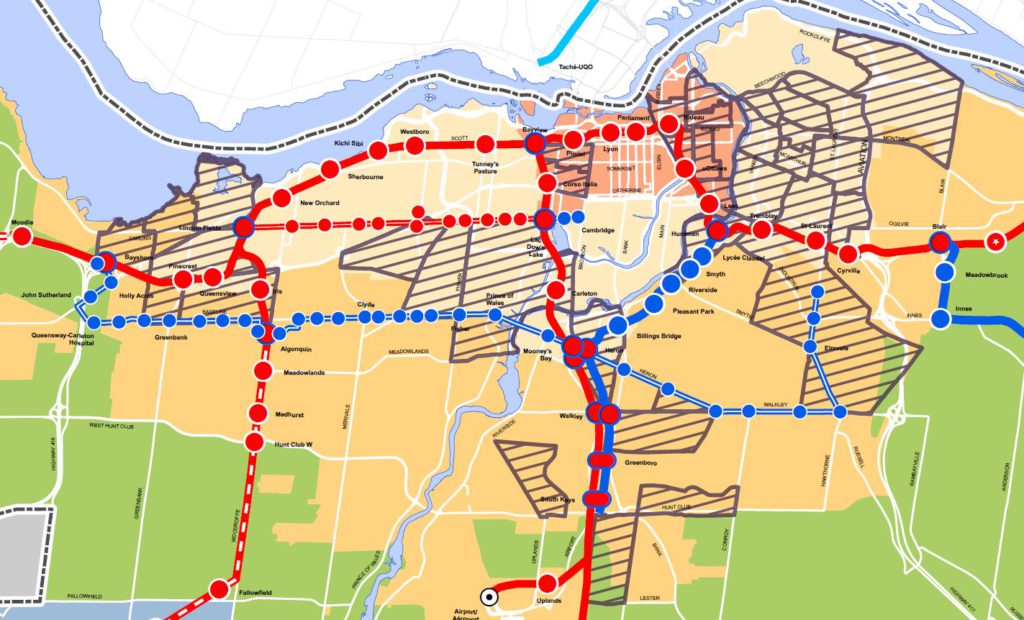

Annex A of the plan identifies “priority neighbourhoods,” which have “high concentrations of residents who are socially and economically vulnerable” and seeks to improve public and active transit infrastructure in those areas. However, the way in which these neighbourhoods are delineated is often incongruous with the routes that commuter cyclists living in them have to take in order to efficiently access their places of work and other daily necessities.

Looking at the map below, we see priority neighbourhoods striped in grey. Some of them appear to be well-integrated into the social and economic needs of their residents, but others, particularly those situated in the suburbs, are quite isolated. For instance, if someone living in Heron Gate, South Keys, or Parkway/Queensway has a job in any of the numerous businesses located along the length of Merivale road, what route are they going to take in order to safely connect them to their workplace? Public transit is not always an efficient option for suburban commuters and in this particular example, it is quite possible for someone to have to take 3 buses as part of their daily commute. Therefore, someone living in one of these communities is likely to resort to active transportation to access many of their daily needs.

I used to be one such person, living in the Parkway area, but working at a business located near Merivale and Hunt Club. While this only constituted a 30–40min bicycle commute, it took 1.25–2hrs via public transit because it required taking one bus across Baseline and two separate buses down Merivale. There are numerous other examples of commute routes throughout the suburbs that involve multiple (and often infrequent) buses, making it more efficient for commuters to get to work by bicycle. However, these routes are far from safe. While working at the aforementioned job, I personally was hit by truck drivers on two separate occasions and another person was killed while riding a scooter directly along my commute route.

In the city of Ottawa’s 2020 annual safety report, the following intersections were signaled as being among the top most dangerous in the city:

- Blair Rd. and Ogilvie Rd.

- Merivale Rd. and Meadowlands Dr.

- Baseline Rd. and Clyde Ave.

- Baseline Rd. and Woodroffe Ave.

- Bank St. and Walkley Rd.

All of these are major intersections located in neighbourhoods with significant low-income populations, and all of them except for Merivale and Meadowlands are on the list of TMP priority neighbourhoods.

Collisions at these intersections have been the cause of countless injuries and, in previous years, have even taken lives (see here and here). If the goal is truly to increase transit accessibility and safety within “priority neighbourhoods”, then one would think that collisions and injury rates would play a role in deciding which roads and intersections receive safety infrastructure for vulnerable road users.

The failure to safely connect active transport commuters with key destinations is a pervasive issue within urban planning, but it adversely affects some segments of the population more than others. Those who do not have access to a vehicle and who cannot afford to live in high-priced downtown cores are often left behind, stuck with excessively long commutes—or worse, forced to turn down jobs due to lack of access. When we look at the City of Ottawa’s list of candidate projects, there is very little to connect suburban “priority neighbourhoods” with the daily necessities of their residents. Short stretches of disconnected and often unsafe active transport infrastructure here and there, but nothing along main arteries that contain most of the businesses and institutions that we all need to regularly access. As much as the City would like to believe that active transport users can always be shoved onto side-streets and recreational paths, tucked away from high-speed traffic, this simply is not the reality—and harbouring such delusions will continue to endanger the safety of the city’s most vulnerable.