The case for lowering speed limit is one that can’t be argued against, and rightfully so — speed is a factor in the severity of injuries and death on our streets. Cities around the world, and the World Health Organization, supports 30km/hr streets.

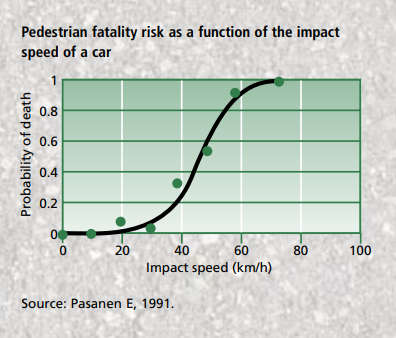

Why? Because lower speeds allows drivers more reaction time, a more full field of vision of the street, and a person’s chances of survival if they are hit by a driver is drastically better. Getting hit by a driver at 30km/hr has a survival rate of 90%, whereas, getting hit by a driver moving at 40km/hr is about 50%.

As part of the 2019 Road Safety Action Plan Update, Ottawa City Council approved the recommendation that “The principles of a Safe Systems approach to road safety in road design and that all new local residential streets, constructed within new developments, or when reconstruction occurs on local residential streets, be designed for a 30 km/h operating speed”. Staff were directed to create a 30km/hr “toolbox” to help in the design of 30km/hr streets.

Wards across Ottawa have seen speed limit reductions – many lowered from 40km/hr to 30km/hr. Bike Ottawa would prefer the city go with a blanket speed reduction (as many cities around the world are embracing, Quebec City is one!), and not leave it to Ward councillors to ask for reductions. Doing so will result in an equitable distribution of 30km/hr streets across the City. A blanket speed limit of 30km/hr will also make it easier for drivers to understand because it will be universally applied.

Simply putting up “30km/hr” signs on wide streets is not enough, street design is key.

Today we’re diving into the City’s 30km/hr Design Toolbox design guide to see what measures are being recommended to create streets that will encourage drivers to drive 30km/hr or less. This Toolbox can help streets become not just 30km/hr streets in name, but also in use.

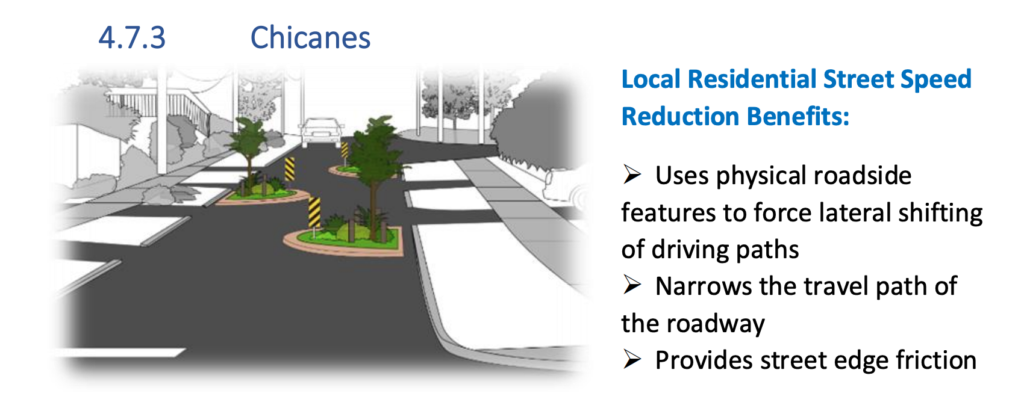

Design elements, including narrowing of streets, “vertical deflection” (raising parts of the street), “horizontal deflection” (such as chicanes that make people slow their car as they curve), and blocking or restricting access (median diverters, closing streets to cars, etc), all work to signal drivers need to slow their vehicles to move through the area safely.

There’s a lot of great suggestions in the Toolbox. It’s clear Staff did their homework, looking at examples of 30km/hr streets around the world and elements that create true slower streets.

The Toolbox identifies the following three different “tiers” of elements that can be used when creating a 30km/hr street:

“Tier 1: A reduced speed is necessary to navigate these physical measures because of their vertical or horizontal nature.

Tier 2: A reduced speed is likely to result because the measures increase the driver’s awareness of their speed.

Tier 3: A reduced speed is likely to result only when these measures are effectively combined with Tier 1 or Tier 2 measures.”

Here are some of things we really like in the Toolbox:

Intersection measures:

Intersections are an important focus when designing streets, as they are the places where there is a greater potential for conflict between drivers and people walking, rolling, and biking. Ottawa now has a design guide for Protected Intersections, which are being built around the city on higher volume streets. Other situations, however, call for different intersection treatments (we’ve written about some of these before: Trillium and Beech is a good example), to create 30km/hr streets, other measures can be used to ensure slower driving speeds.

Here are some good examples the City has in their design guide (all pictures are from the Toolbox):

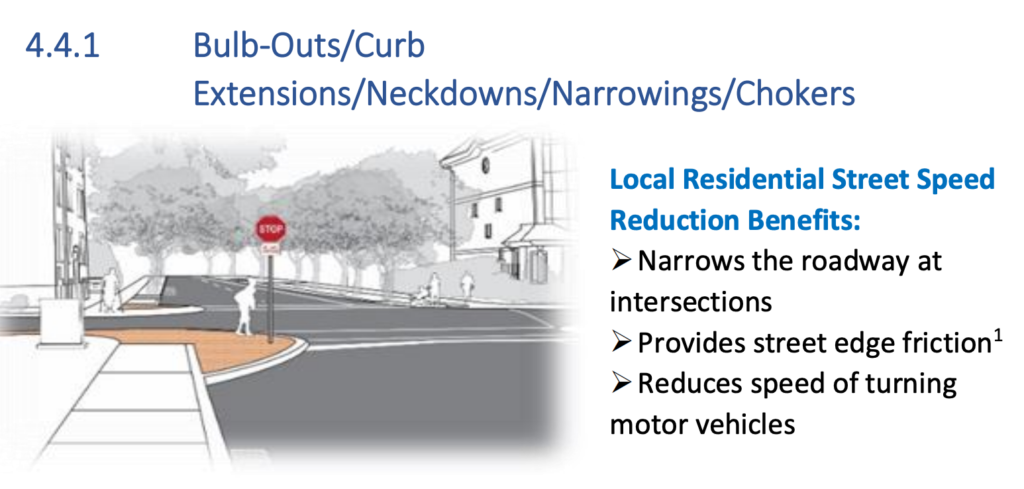

Bulb-Outs/Curb Extensions/Neckdowns/Narrowings/Chokers:

These features provide “street edge friction”: design that influences how drivers perceive and respond to a street—meaning, a narrower street creates a perception of confinement and results in a driver lowering their speed. These elements help improve visibility of people outside of cars, shorten crossing distances, and provide opportunities for more greenery in the right-of-way.

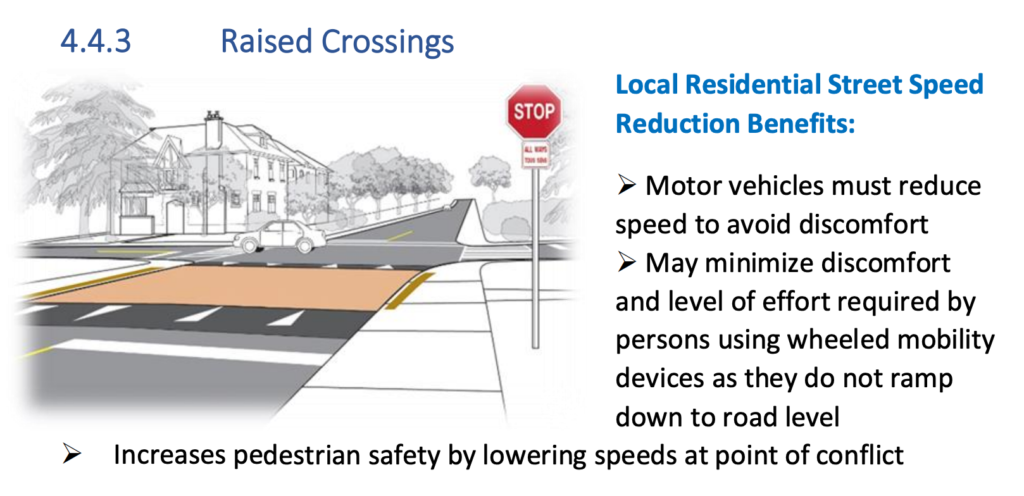

Raised Crossings and Raised Intersections:

Raising crossings at intersections encourage drivers to reduce speeds in order to minimize their own discomfort, and decrease the likelihood of serious injuries or death for people outside of cars. Raised intersections and crossings can also benefit people using mobility devices, as they do not need to contend with uneven surfaces. They are also easier to maintain in winter and are less likely to have snowbanks at pedestrian and bike crossings.

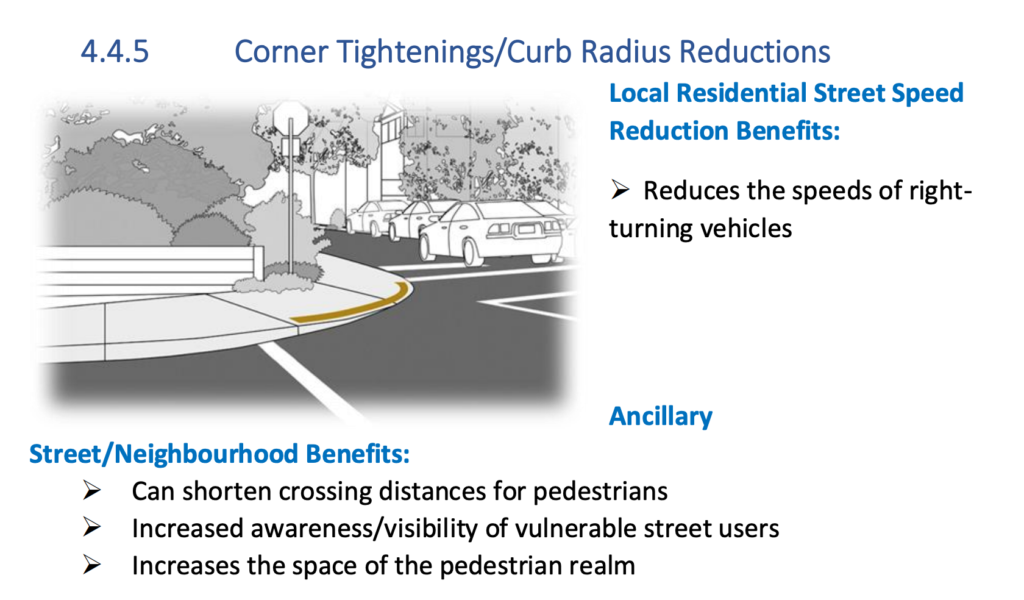

Corner Tightenings:

Tighter turn radius means drivers need to slow their vehicles to negotiate the turn, increasing the margin of safety for those outside of cars in the case of a crash. Tighter corners also mean shorter travel distances for people outside of cars to cross streets, and it also increases the visibility of those outside of cars.

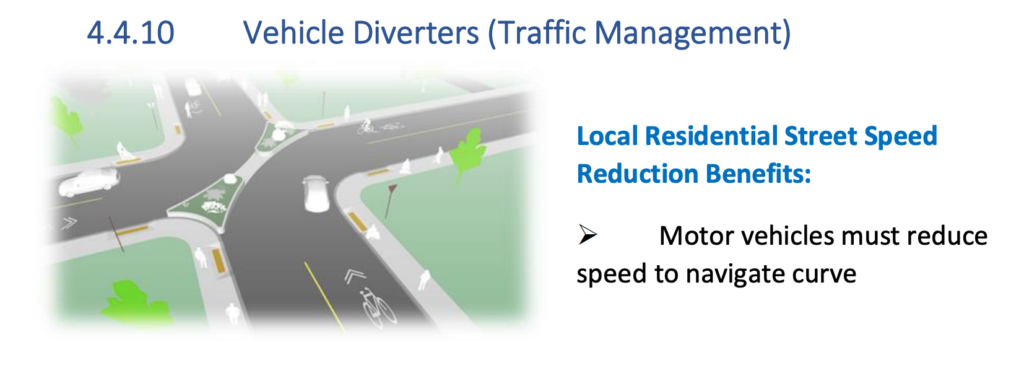

Intersection Channelizations (Traffic Management):

Designs such as “Vehicle Diverters” and “Raised Medians Through intersections” manage car traffic by reducing speeds and reduce “cut through” car traffic, redirecting drivers to collector and arterial roads instead of using local streets.

Street Edge Measures

Chicanes help narrow streets, creating “friction” for drivers, resulting in lower speeds.

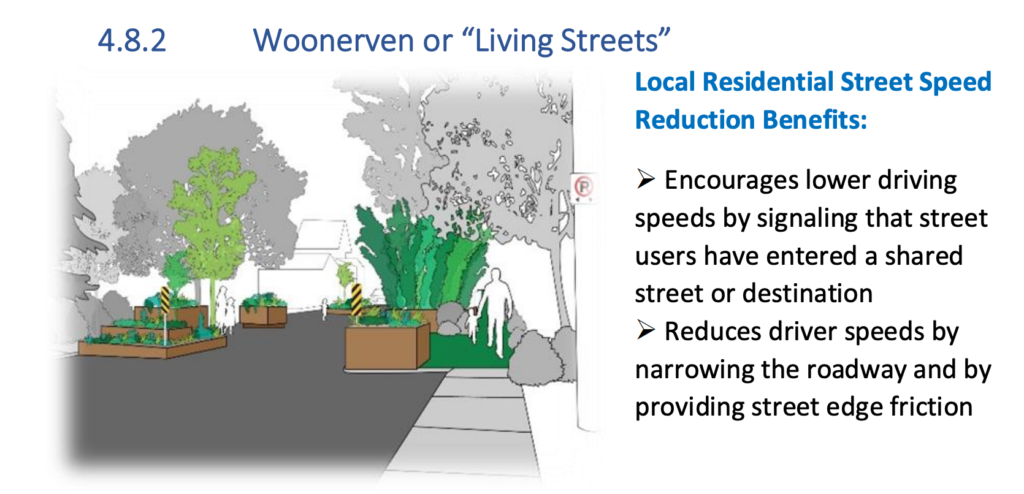

“Emerging Measures”

“Emerging measures” in the Toolbox include design elements such as Continuous Footways/Bikeways, Woonerven or “Living Streets”, “Shared Spaces”, and Traffic Buttons (think mini roundabouts). These measures come with a caveat in the Toolbox: “The following emerging measures are not typical and local examples may be limited to pilot projects only or referenced from other municipalities. At this point they are conceptual measures to be considered in designs going forward.”

It’s encouraging to see these types of elements included in the design Toolbox, and we hope those designing 30km/h streets will be implementing them, as they not only provide a higher level of safety, but create healthier and more liveable streets.

HOWEVER, here’s the concerning part:

Part of “Tier 2” suggestions for Street Edge Measures (narrowing the street) includes the use of on-street car parking.

Parking is the poorest level of traffic calming and should not be part of the 30km/hr toolbox. Taking a look at the CROW Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic, car parking is never mentioned as a safety measure, but a risk factor, creating potential danger on streets. For example, parked cars increase the risk of getting “doored”, and blocking sight lines of people on sidewalks. Parked cars are in fact a hazard, not a safety improvement, and the hazards far outweigh any marginal benefits of reducing driving speed.

The Toolbox suggests that parking areas “When not in use, provides additional space for other uses such as cyclists and snow storage”, relegating space for people on bikes to an iffy at best scenario. While people on bikes might move into the parking lane, this also means their path of travel can be blocked by either a parked car or a bulb out, forcing them to weave and move back and forth in the lanes. This is especially true if the measures of alternating on-street parking are used. Again, the Toolbox suggests these as a way to “create lateral shifting of diving paths” but the end result for people who bike is constant shifting and weaving down the street, making their path of travel less predictable and less safe.

This isn’t to say you can’t ever build streets with on-street parking, they exist sometimes, but here’s a juxtaposition of what could be (left), and what we’re currently seeing in Ottawa (right).

Both of these photos have on-street parking and are

traffic calmed, but which one do you think results in a realized motor vehicle travel speed of 30km/hr or less?

Currently in Ottawa, we’re seeing a lot of flexposts for traffic calming- what the Toolbox calls “Vertical Centreline Treatments”, “On-Road Messaging”, and “Educational Campaign” elements including the green, blue and white “Slow down for us!” and “Traffic-Calmed Neighbourhood” signs.

At best, flexposts are a seasonal deterrent for drivers to slow their vehicle speeds but even then, these posts are easily driven over and often destroyed by motorists, making their utility limited.

These measures are included in the “Temporary Traffic Calming Measures Program.” Each Councillor is allotted an annuual budget of $50,000 for these temporary (read: Seasonal) measures. But $50,000 doesn’t buy much when you consider the size of streets, Wards, and the sticker price of

It is also becoming more common to use painted messages that state 30km/hr speed limits or designating school zones, but we know signage is easily ignored. “Slow down for us!” signs and “Education campaigns” are ineffective; we know a true Safe Systems approach does not focus on signage, but on design.

A true 30km/hr street will encourage motorists to drive 30km/hr or lower, and will lead to a more comfortable setting, where people on bikes feel safe riding a bicycle, or taking a stroll. The new tools in the City’s Toolbox provide plenty of great design solutions to make slower streets a reality, but as with all traffic calming projects, adequate funding is needed to make them an all-season reality.